Humans can survive without food for weeks, sometimes months, but only 3 to 4 days without water. We are water: 60% of our body is made of this transparent liquid of which we are helplessly dependent. Although it is number one in our hierarchy of basic human needs, we rarely go thinking about water beyond our morning shower or our recommended 8 glasses per day. As a fashion creator and a citizen of the internet, seeing the subject of fashion sustainability popping up more and more often in my news feed, I started thinking about water in its relationship to fashion. What is really happening?

The facts

The fashion industry is the second most polluting industry in the world after the Petroleum industry. Cotton, one of the two most popular fibers found in our clothes today (the other one being polyester), although amounts to only 2.4% of the world’s cropland, consumes 10% of all agricultural chemicals and 25% of insecticides. These chemicals entering the soil contaminate fresh water and destabilize ecosystems.

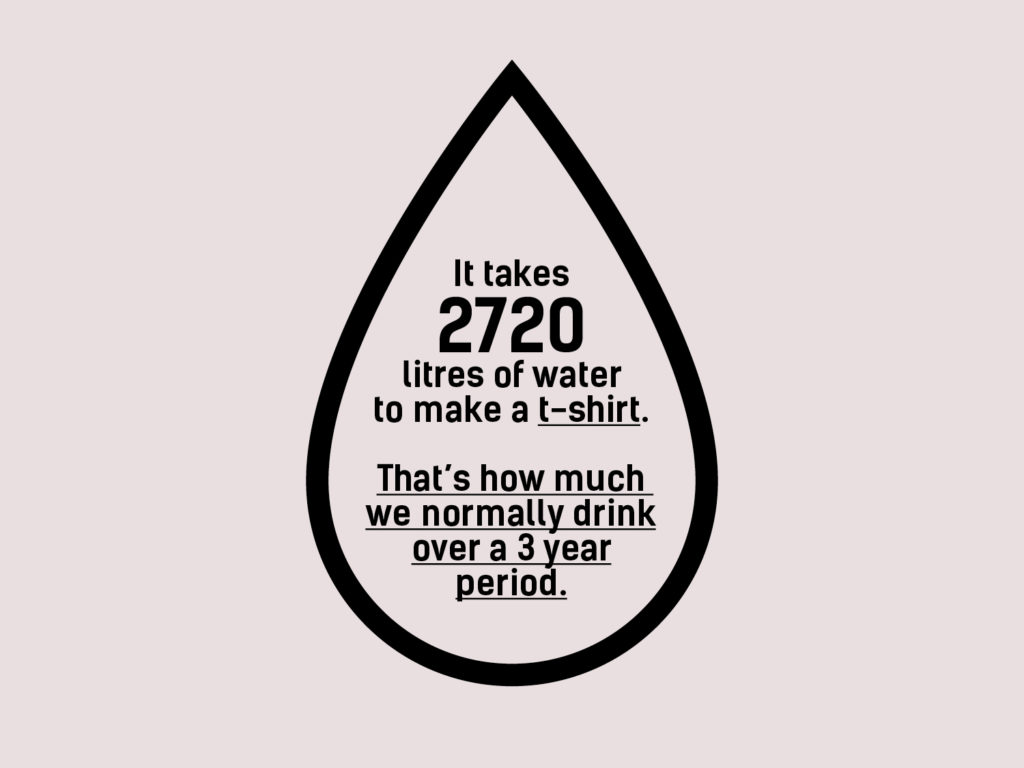

More than a half trillion gallons of fresh water are used in the dyeing process of textiles each year, amounting to 20% of global industrial water pollution. It takes around 7,000 liters of water to produce one single pair of jeans – equivalent to the amount of water one individual drinks in 5-6 years. In India and Bangladesh, dye wastewater is discharged, often untreated, into nearby rivers eventually spreading into the sea. Reports show a dramatic rise of diseases in these regions due to the use of highly toxic chrome. In China, the world’s largest clothes exporter, the State’s Environmental Protection Administration declared that nearly one third of the countries’ rivers are classified as “too polluted for any direct human contact”.

A 2017 study discovered microfibers coming from plastic and polyester in 83% of all tap water samples around the world. In Germany, microfibers were found in 24 mass-market beer brands, in honey and sugar. Fish and shellfish in markets around the world were found to contain microfibers. A 2016 study from University of California found that an average of 1,174 milligrams of microfibers are released from our washing machines after washing a single synthetic jacket. But microfibers are not only found in fleece. They are inside half of the world’s clothes, in polyester, nylon or acrylic fabrics and the numbers show synthetic fibers will be more and more popular in the future.

The situation looks bad. But isn’t there enough clean water on Earth? 70% of the world’s surface is covered in oceans.

97.5% of the water available on Earth is found in oceans as saltwater. In order to turn it into fresh, drinkable and usable water, saltwater needs to go through a process of desalinization. Although there are countries (United Emirates, Israel) who are already using desalinization due to lack of access to fresh water sources, the costs for such operations are double than the ones for processing fresh water. Thus, the solution is not viable at the moment for many of the poor countries already exposed to water scarcity. What scientists are hoping for is that renewable energies evolve in such a way that desalinization becomes affordable. But we don’t know yet if and when will this happen.

What about the other 2.5 percent fresh water left?

2.5% of the water on Earth is fresh, drinkable water. Of this 2.5% two thirds is frozen as snow and ice (and it better stay that way) and more than one third is found as groundwater. That leaves us with 0.3% fresh water available in rivers and lakes. This water is used in households, in agriculture and in industry. Although 0.3% is a large amount compared to the Earth’s scale, research shows that we are consuming the available resources at 1.6 times the planet’s capacity.

How much are we consuming?

Clothing production has doubled since 2000, yet 40% of the clothes we buy are rarely or never worn. In North America only, 10.5 million tons of clothing are sent to landfills every year. From the average of 118 clothes found in a German closet, every 5th garment is never worn. If it is a jacket, coat or dress, it will stick around for around 3 years. If it is a T-shirt, pair of trousers or shoes, it will be thrown away after less than a year. Trend are changing faster than ever: based on the number of new items reaching its stores weekly, Zara was registered to have in 2014 a number of 52 micro-seasons.

How did we get here?

Before the 19th century, dressmaking was far more complicated than it is today: in order to have a blouse, a middle class person would have to raise sheep, collect the wool, spin the yarn, weave their own cloth, then sew their piece by hand. People of higher status would go to a couturier which made their clothes to order. The Industrial Revolution introduced the sewing machine and changed the fashion industry into something closer to what we have today: clothes made in bulk, in universal sizes, in big factories. But it wasn’t before the World War II, which imposed restrictions in fabrics and more functional clothing, that people changed their mentality towards fashion and started to fully accept standardization.

Once clothes became cheaper to make, and thus, accessible to masses, it became tempting for fashion to become a business of quantity, rather than of quality. The formula was simple: the faster you produced, the more you sold, the more you earned. It is not clear which was the first brand to adopt the fast fashion philosophy. Looking from a longevity perspective, H&M opened its first store in Sweden in 1947, while Zara launched in northern Spain only in 1975. But when Zara reached the U.S. at the beginning of the 90’s, The New York Times used the term “fast fashion” to describe the incredible speed at which the retailer was able to transform a design into a final product: 15 days.

But how can you sell new clothes to someone who has already bought new clothes two weeks ago? By inventing a new trend. This all comes hand in hand with the needs and tendencies of the human psyche. Being ”in trend” fulfills our need for certainty, consistency and belonging. But once we have all these needs fulfilled, the need for variety comes in. New trends are able to miraculously make us feel we have variety and certainty in the same time. And once trends start moving faster and faster, this wheel of needing and fulfilling our needs spins, reaching the speed of today’s 52 micro-seasons per year. It’s no wonder that around 40 percent of consumers qualify as excessive shoppers, going shopping compulsively more than once a week, as a worldwide study by Greenpeace reveals.

What can we do about all this?

Despite the responsibility of governments to regulate companies’ practices and protect the environment, in a world ruled by supply and demand, customers can play a crucial role. It can be discouraging for an individual to look at the immensity of our global issues and think one’s choices can really help to bring change. But something is certain: no matter how big or small our actions are, they will either contribute to the problem or to the solution. There are many things that we can do. Here is a small selection of them:

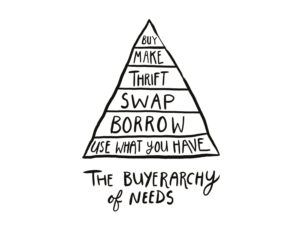

- We can buy less. We can start borrowing clothes between friends or we can participate in clothes swaps. We can also practice our creativity by upcycling our existing clothes to create new designs.

- We can buy better. We can start looking at clothes as long-term partners and dare to pay more for a piece that will last longer. We can search for sustainable fabrics and quality brands, which take care of the environment.

- We can buy second-hand, contributing to a lower demand for new clothes and thus, to less production.

- We can take better care of our clothes. We can refresh clothes that aren’t stained, instead of washing them just because someone smoked next to us. And when we wash polyester garments, in order to reduce the microfibers released in the water, we can keep the temperature at 30 degrees. Also, washing a bigger load is better because it gives less room to microfibers to detach from clothing.

- We can search for our own style, regardless of trends. A good starting point is to analyze the items that we wear most often and ask ourselves why. This way, the next time we will go shopping, we will be able to choose only the things that we know we will wear.

Written by Cristina Tatar @cristinacristina

References:

9 Antworten auf „Fashion pollutes water. Should we really care?“

[…] [6] https://future.fashion/fashion-revolution-day-germany/fashion-pollutes-water-should-we-really-care […]

[…] pic credit https://future.fashion/fashion-revolution-day-germany/fashion-pollutes-water-should-we-really-care […]

[…] which enters the earth and ends up in our water streams. Textile water pollution accounts for 20% of global industrial water pollution due to contaminants like […]

[…] used in the dyeing process, which amounts to about 20% of the global industrial water pollution. Reports have shown that there has been a dramatic rise of diseases in regions due to highly toxic chrome. In China […]

[…] to Future Fashion, the fashion industry is the second most polluting industry in the world after the oil industry. […]

[…] Forward. 2018. Fashion pollutes water. Should we really care?. [Online] Available from: https://future.fashion/fashion-revolution-day-germany/fashion-pollutes-water-should-we-really-care [Accessed: 5 October […]

[…] More than a half trillion gallons of fresh water are used in the dyeing process of textiles each year, amounting to 20% of global industrial water pollution. It takes around 7,000 litres of water to produce one single pair of jeans – equivalent to the amount of water one individual drinks in 5-6 years (source). […]

[…] low-quality, affordable items consume 7,000 gallons of water, you don’t want to be part of the problem when some people in the world have no […]

[…] that is used to dye the jeans, it is emitted back to the nearby rivers. Due to the chemicals, it increased the risk of diseases in the […]